Percentages Are Misleading

Two days ago, I got a text from someone who wanted me to quote a monetary value of a dinosaur skeleton for them. It read, “How much is a 60% complete trctertops (sic) worth?”

I initially reacted with, “Which 60%?” but I stopped before I sent the reply. I know that it matters which portion of the skeleton is present, but I don’t believe this person understood that. Still, I hear this question more and more and I need to address it. Using percentage completeness of a skeleton is misleading at best, ignores other metrics that matter more, and does not properly evaluate the value of a skeleton in either economic or scientific terms. Better metrics exist.

The reason I distrust the percentage valuation equation stems mostly from the fact that you must clarify what percentage means. Are you referring to the mass of original bone material recovered or the number of bones recovered? This is an important distinction because depending on how you look at it, all bones are equal to one another…unless they’re not.

Let’s play around with some numbers. To demonstrate this, we at the shop took a small tyrannosaurid cast skeleton packed loosely. It has 264 bones in it. I’m operating under the assumption that since density is consistent across the cast bones, they’re simple to compare. Fossil bones from a skeleton tend to be consistently dense so although this isn’t an exact science, it can still demonstrate a lot.

We weighed sections of the skeleton by groups. Dorsal vertebrae, caudal vertebrae, right side dorsal ribs, etc. We tallied everything up, counted all of the bones, and plugged everything into a spreadsheet.

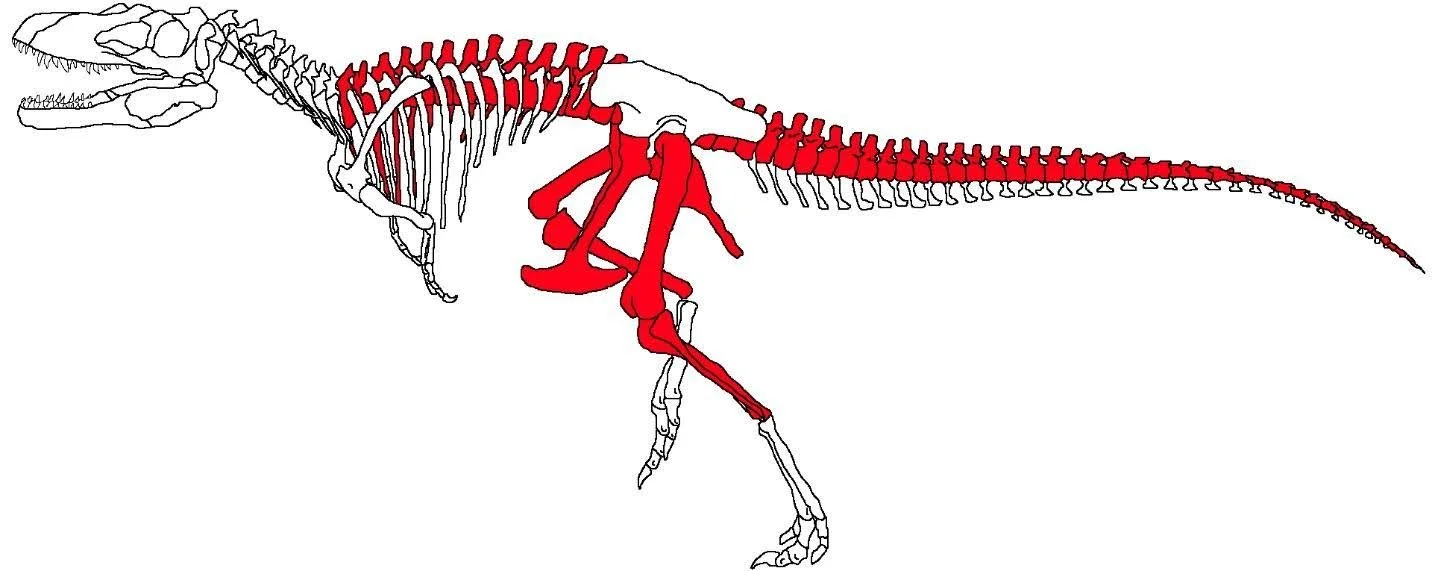

Now let’s look at a hypothetical example skeleton. Pretend we just finished preparing this in the lab and we’re excited to do a layout and see what all we’ve got. Here we’ve got the entire dorsal vertebral column, the sacrum, the tail vertebrae (but no chevrons), right side body ribs, the ischium and pubis from each side, as well as both legs from hip to ankle. That means we’ve only got the paltry count of 82 bones out of 264. By the numbers, this skeleton clocks in at a disappointing 31%.

However, when we weigh each of these bones, we find that they account for 67% of the mass of the skeleton. So, which is it? Is it 31% complete or is it 67% complete? The answer depends largely on which side of the negotiating table you’re sitting at.

If you’re selling a skeleton, you will pick the method that yields the bigger number and use that to drive up your price. If you’re buying a skeleton and you’re savvy, you’ll do some of your own arithmetic and go with the 31% metric and try to drive the price back down. Neither number is technically wrong, but since they aren’t comparing the same thing, neither one really tells the truth.

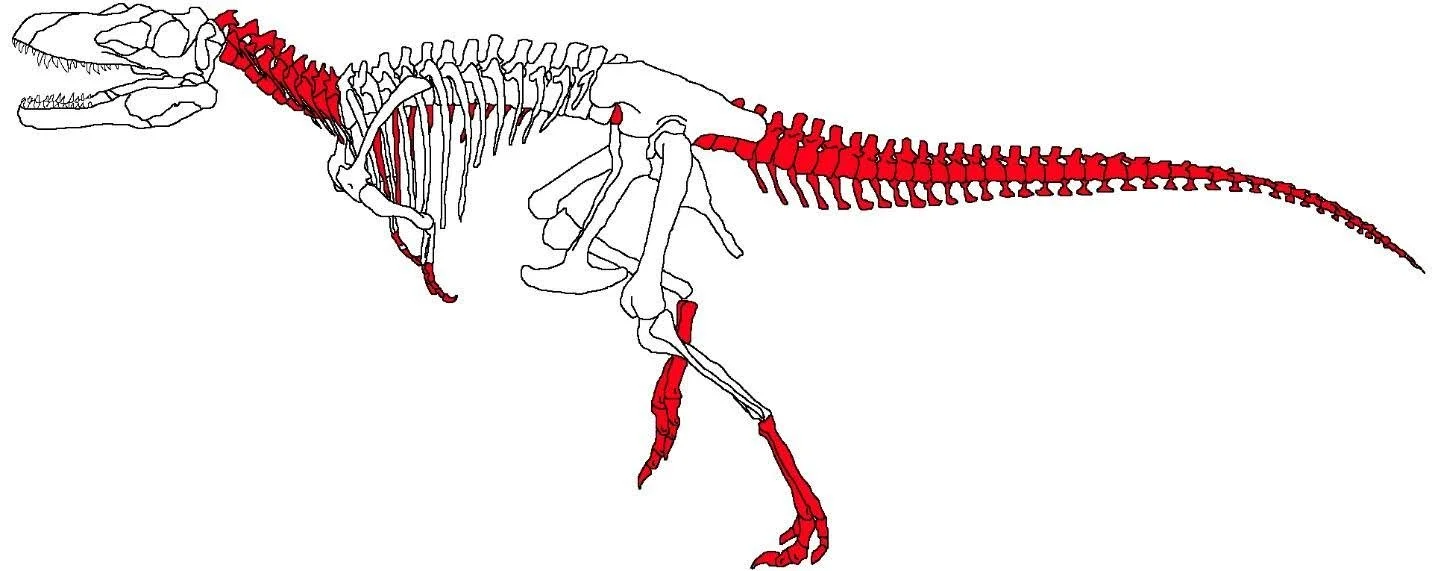

Here’s another one to drive the point home:

This one has 181 bones represented out of a possible 264, which means that it is a spectacular 69% complete. Do you see how I arrived at that number? I counted all of the tail vertebrae and each tiny chevron on the underside of those vertebrae. If I go by mass, then this skeleton is only 45% complete since I only have smaller bones. Which metric would you pick if you were trying to scam an unsuspecting newcomer to fossil collecting?

Please note that in both of these examples, the skull is missing. Large sections of the skeleton are missing. These are each nice finds and they have value, but the numbers are easily inflated and misrepresented and you still won’t get what you’re looking for.

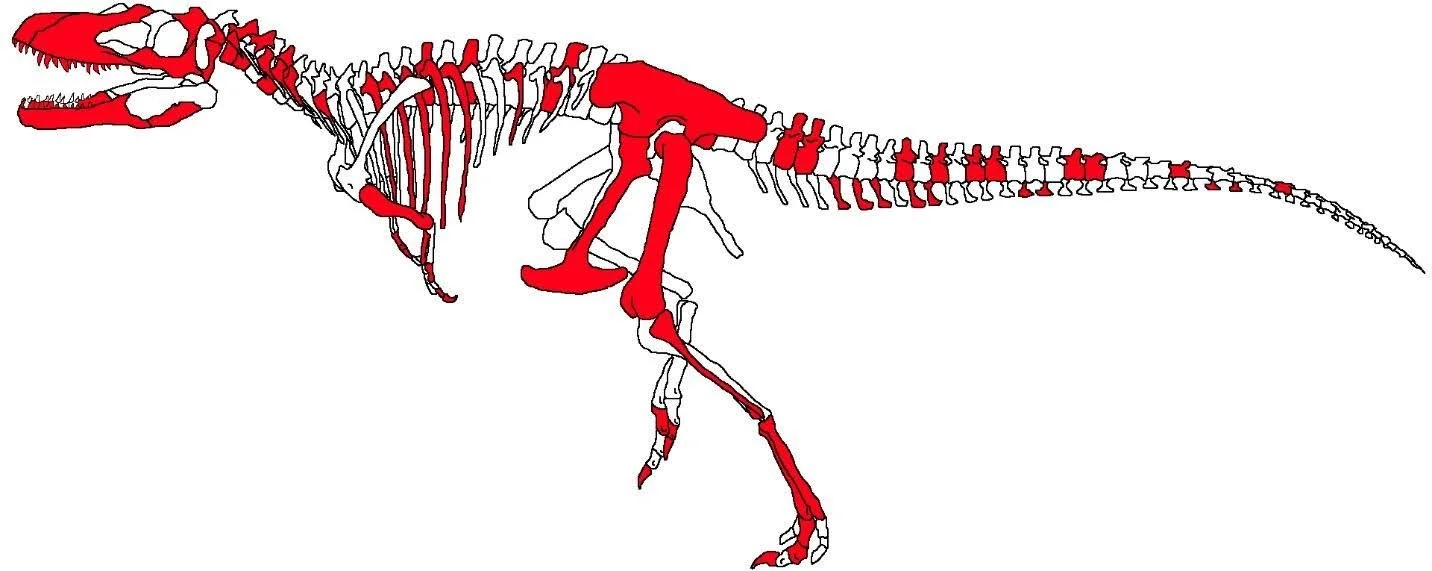

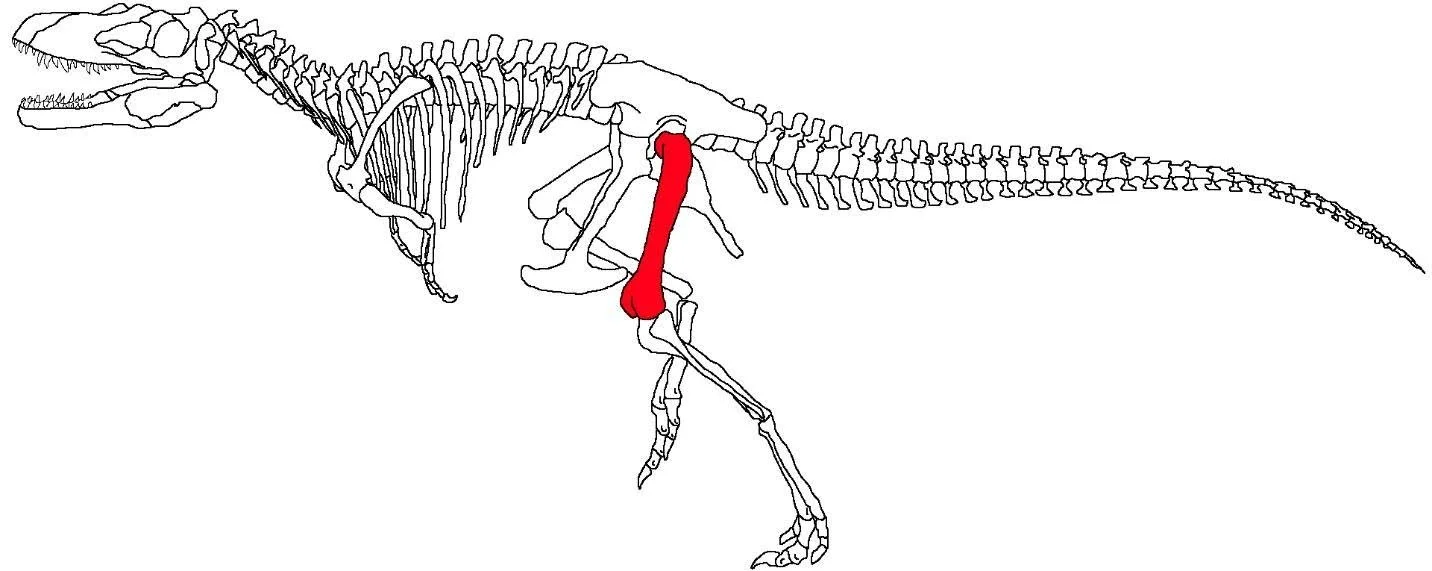

Now let’s look at a skeleton that a collector or a scientist is likely to be more interested in:

Notice how there are representative portions of every part of the animal. We’ve got a leg, arm, vertebrae and ribs, tail bones, lots of the hips, and even some really nice skull material! With modern 3D scanning and printing technology we can mirror right and left bones to fill gaps for display. If we’re more interested in the research value, we get a better understanding of what the entire animal actually looked like. However, by bone count it is only 25% complete. Compare this to the skeleton in Figure 2 and it’s not hard to figure out which one is more valuable commercially and scientifically. Percentages are irrelevant in this case.

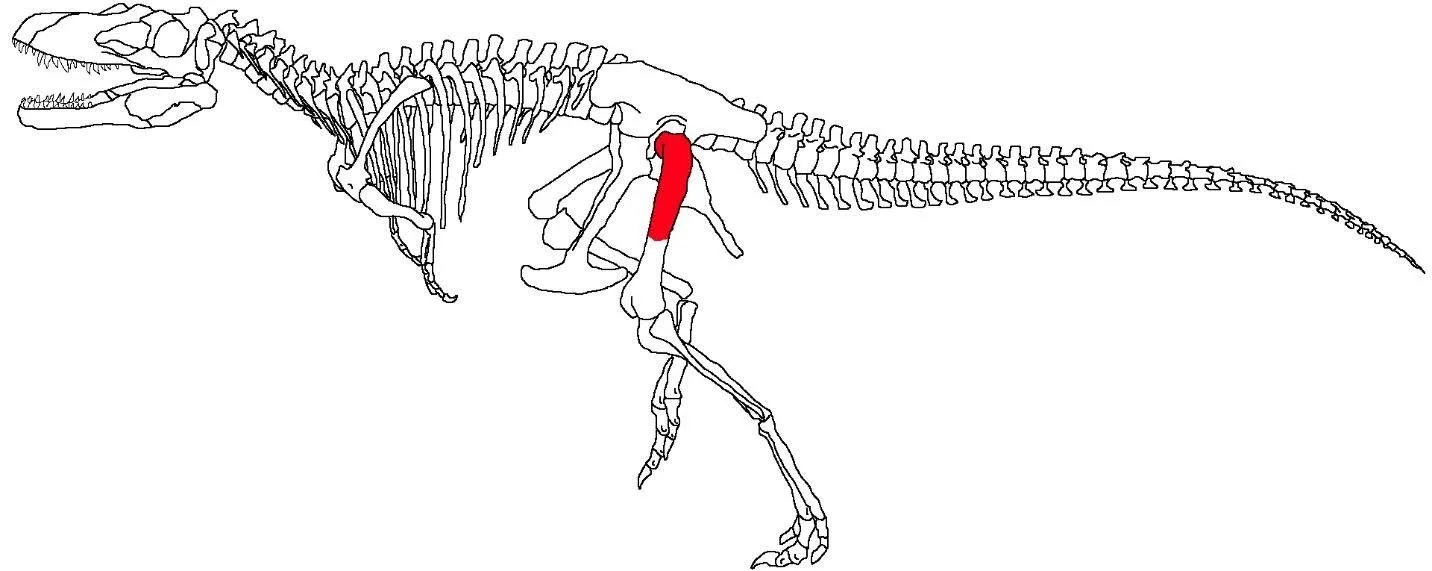

Let’s look at one more example of how numbers can be manipulated. Bones are frequently incomplete. Scavengers back in the Cretaceous wanted their meals and many of them could bite through bone. As fossils erode out, weathering takes its toll and destroys fossil material. A lot of forces work against us ever finding something in good shape. It’s not unusual, for instance, to find an incomplete femur:

Figure 4 Incomplete bones should be represented as such.

The distal end of the femur wasn’t preserved in this case. If a seller is honest, they’ll represent what was actually preserved. If they are not, they’ll fill the whole bone in and never tell you:

How would you know whether they filled in the missing part without specialized tools and experience? The only other way is if they tell you. Multiply this example across an entire skeleton and suddenly your “percentage complete” score becomes even less informative. If someone has every bone completely filled in over a whole skeleton, they aren’t being honest with you.

A perfect example of this problem was a Triceratops skeleton that recently went to auction and commanded several million dollars. Within minutes of the announcement of the auction, fossil enthusiasts all over social media had picked it apart and could tell that the skull had obviously been fabricated by gluing random fragments of bone together in a vaguely skull-shaped mess. The buyer didn’t know much about fossils and didn’t find out until after the deal closed.

Please keep in mind that in all of my examples the numbers were actually calculated. I’ve worked professionally in vertebrate paleontology for a little over 20 years and have never seen someone bust out a spreadsheet or a calculator to generate figures. When asked, people always look up to the left for a few moments and then say something like, “I’d say it’s about 65% complete.” They’re making numbers up. Always ask people to show their work if you’ve got real money on the line.

So, what should you do? How do you evaluate a fossil?

Other metrics determine what the fossil means to us. Some bones are more diagnostic than others. Some bones, like a furcula (the wishbone), are more interesting and scientifically important than others, like the chevrons cited in the above example. One skeleton may be preserved in amazing shape with excellent surface quality, great preservation that makes thin sectioning possible, or even contain skin impressions. Another skeleton may be from an animal that sat in stagnant water for a month before getting buried, was heavily scavenged, and then sat on the surface for 50 years before anyone found it. If the scavenged skeleton is more complete, is it really more valuable? Preservation quality matters.

There are more and better ways to evaluate a fossil than by percentage completeness. I’ve got two questions that I like to start with when evaluating a skeleton:

“Exactly which bones do you have preserved?”

and

“What kind of shape are they in?”

From these two questions, I can ask all sorts of follow-up questions and have a fun conversation about a fossil. The answers I get will tell me something about the true nature of a skeleton, what it could mean in the broader scientific context, and even a little bit about the potential monetary value of it.

If you ask the above two questions of someone and they evade it and try to bring you back to a conversation about percentages, then bust out your UV light to examine what they’ve got versus what they’ve sculpted. Then go elsewhere. That person is not being honest with you.

It’s tempting to look through a collection of fossils and want a singular number that sums up quality in a nice, digestible format. That number does not exist.

It takes a little bit more work to learn the names of the bones and how to really look at them, but not a lot more work. Plus, learning about fossils is fun! Think of it like art. If you go into a museum and look at paintings, it can be an enjoyable experience. If you’ve learned some of the historical context and the story of the artist, the painting suddenly becomes more meaningful and you’ll spend more time observing it. Treat your interest in fossils like this and you’ll find better deals, have more fun, and you’ll have a lower chance of getting scammed.

If you need help or advice about this subject, as well as training materials I use to teach my staff about dinosaur anatomy, then please reach out. A more informed and discerning audience in paleontology is the best thing for everyone, academic and commercial alike.

###

Jacob Jett

Vice President, Corporate Development and Sales

jacob@rmdrc.com | (719) 394-3212